Injured Abroad My wife’s nasty accident while travelling alone in Asia

On Feb 2, 2010, my wife was severely injured in a car accident while travelling alone, about 50 kilometres east of Vientiane, Laos. Three days later, she was found in the basement of a shabby hospital, strapped to a spine board, barely cared for. An Australian physician found her, and I got The Call from him as I was emerging from a pub in Vancouver, trying not to feel anxious that my wife was at least a day overdue to check in with me, bracing myself for a restless night of probably-unnecessary worrying.

What followed was by far the most shittiest and most transformational experience of our lives so far … and yet I did not write it down until now, more than fifteen years later! It’s a strange omission in a writer’s life, where everything else of any importance that has ever happened to me has quickly found its way to my keyboard.

It’s time to tell the story at last. Better late than never.

I will be using a pseudonym for my wife. She is quite shy about online exposure, and more so with every passing year.

The doctor could only tell me that Amy wasn’t in immediate danger of dying, but the situation was dire: she was lying, virtually uncared for, with multiple severe injuries, including head and spine. While she was rushed to a hospital in northern Thailand, I rushed to meet her. She lived and she was not paralyzed, and in the short to medium term she did quite well; but it was an extremely close call and there still are serious long-term consequences, unfortunately. Her main injuries:

- severe head injury

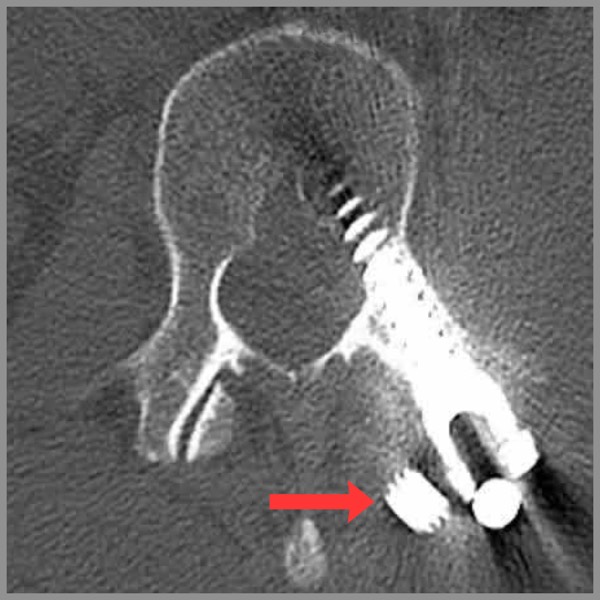

- severe burst fracture of T12

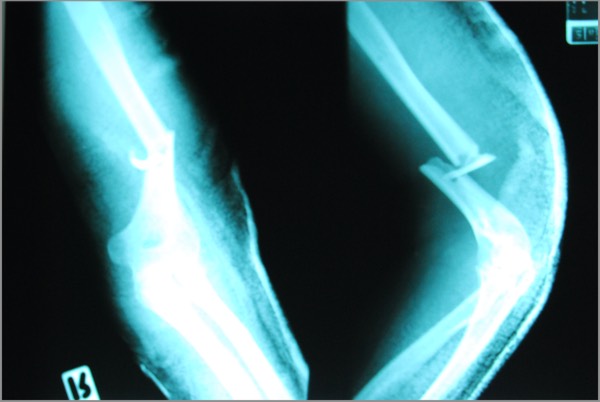

- severe closed comminuted fracture (4 fragments) of right upper humerus

- moderate lacerations to the scalp and right shin

- minor fractures of the right ankle, and the right pubic bone

- a broken tooth

I slept in her hotel room with her for a month, nursing and managing the logistics of getting her home. Our flight with a medical escort was the most expensive thing we’ve ever purchased.

Big lessons learned

As with everything I have ever written, I hope this very personal story might be useful to some; perhaps it will give some comfort and insight to someone else facing a similar ordeal. In that spirit, I will begin with a few things about this experience that made me older but wiser:

- Travel insurance isn’t optional. Do not travel without it. Just don’t. The big expense no one thinks about? Medical escorts are astronomically expensive but virtually unavoidable, because airlines are amazingly reluctant to fly significantly injured passengers.

- Even relatively minor head injuries should be taken seriously, and care to mitigate their consequences should be proactive. Overall health, fitness, and clean living are essential.

- Healing from major injuries is utterly exhausting. Prepare for many months of greatly reduced energy levels.

- The emotional stress of a situation like this is nothing to mess around with either. This is the life situation that proved to me that stress can become so severe that it’s like a poison.

- If you simply have to get injured while travelling, do it in or near Thailand. Healthcare there is a terrific value. 😉

The accident

Amy was riding in the back of a pickup truck, getting a lift, as one does in the countryside of Laos. She was sitting on a plastic chair, snapping photos of the countryside on her first iPhone. We have an eerie series of photos leading right up to the minutes or even seconds before the accident.

No one knows exactly what happened next, or ever will know. Amy has never recovered any memory of the accident at all, and not much leading up to it or for days after. She remembers a fan spinning lazily in the basement of the hospital in Vientiane. That is more or less it, just one lonely image from the moment of the accident until four days later when we were reunited. The whole month of February 2010 is just a smear of impressions and isolated scraps of memory for her, and later we discovered that significant events for months before the accident had also been destroyed by the impact.

We know that the men in the cab of the truck were also severely injured, and one probably died, but we have never learned any details of their fate. It was a work truck for a company that disposed of the unexploded ordnance that litters Laos — a bizarre, awful legacy of the Vietnam War.

Wounded and lost in Laos

As far as we know, Amy was probably transported to the hospital in Vientiane relatively quickly, but once there she received only immediate critical care. She was on a spine board and given fluids; her badly fractured right humerus was casted. And then she just lay there, unidentified, barely conscious, and barely cared for.

Mental images don’t get much more disturbing than a loved one in this state. The idea of it has haunted me ever since.

Some good samaritan reported the presence of an “unattended English-speaking woman” to the Australian consulate. They sent their physician, who found her in the basement, just lying on one of many beds. The conditions in the hospital were poor. They couldn’t do anything more for her.

Amy was just conscious enough to recite my phone number, which was a minor miracle.

And where was I? Why was my wife alone in Asia?

The worst phone call ever

I was at home in downtown Vancouver, Canada, working hard. I had just “quit my day job” as a massage therapist at the end of 2009, and was taking my first steps trying to make a living as a writer, selling e-books on a website I had been working on for a few years. It was the most stressful and challenging period of my life up to that point. Although the business was up and running and more or less paying the bills already, I have never had a more urgent need to work hard… which is why I was at home while my wife was travelling. Hell of a time for a crisis.

I also just don’t like travelling, and I’m not good at it — because of a sleep disorder that makes jetlag hellish — which is too bad, because a trip to Asia was about to become mandatory.

I was leaving a pub when I got the call. It was about 10 pm on a Tuesday. I hadn’t heard from Amy for about three days, and was growing concerned. These days, we have the technology to be in constant contact, which is a blessing and a curse. Back then, it was just “I’ll find an internet café every couple of days to check in.” If she failed to check in, I had to go on faith that she was just off the grid longer than expected. But three days was getting on the long side, and worry pounced on me like a cranky cat the moment I emerged from the distraction of visiting with a friend. When my phone rang, I was thinking things like, Well, how long do I wait before I do something? And what exactly would that be?

I remember correctly interpreting the nature of the call. A call from Laos, an unfamiliar man speaking… ruh roh.

He got right to the point, tactful but efficient. I think perhaps he’d made similar calls before.

“I’m here with your wife. She’s badly injured, but she is conscious and she gave me this phone number and your name. You can speak to her in a moment.”

He didn’t really know anything except that her injuries were fairly severe and involved a broken back and possibly neck, and she wasn't being properly cared for. The hospital was just not equipped for it. She was basically in storage with severe but unknown injuries.

I spoke to Amy only very briefly on that call. She croaked out a greeting. She tried to reassure me! But we wouldn’t have a real conversation for days.

The transition to Thailand … still on spine board

The crisis started late in the evening on a Tuesday. And there wasn’t much to do for the first day except worry hard — harder than I’ve ever worried — and wait for updates. One of the earliest updates hinted that her neck might be broken, and for most of a day we lived with that ominous information before it was retracted. Her injuries were severe, but her neck was not broken, “just” her back.

But she was still on a spine board.

Laos does not have much of a medical system, while Thailand has one of the best in the world. So the first step was to move her to a private hospital in Udon Thani, a small city in northern Thailand, and the Australian doctor was able to arrange that almost immediately. He even accompanied her on the ambulance ride to Aek Udon Hospital, and she was “settled” there by our Wednesday morning.

I remember struggling to call the hospital. Connections were sketchy and no one there seemed to speak much English. For a while I was concerned we wouldn’t be able to reach Amy at all.

But we finally got through, and Amy’s mother and I were both on the first successful call. Amy seemed surprisingly cheerful and alert — that was a big surprise — and she was able to confirm that she wasn’t (yet) paralyzed or in imminent danger of it as far as she knew. That was encouraging. Unfortunately, we also heard her scream when she was moved a little — still on the spine board, for at least five days at that point — and that was about the worst thing either of us had ever heard. Maryanne could barely speak for a while.

Surgery there or here?

That was the big question for all of Wednesday and Thursday, and that was why it wasn’t immediately obvious that I would be flying to Amy’s rescue… because we might pass each other over the Pacific Ocean.

I feel like I spent those two days on the phone, having endless conversations — many of them largely futile, in retrospect, but I had a desperate need to be as involved as possible — with the insurance company, Aek Udon Hospital, doctors, the Canadian embassy in Thailand, travel agencies, and so on.

What actually mattered was the insurance company’s medical team. It was their call, and they were busily consulting with Aek Udon hospital, and everyone decided she could be flown home to Canada, but it still wasn’t clear if she should be. Flying badly injured people is logistically nightmarish, and any bureaucratic delay could be dangerous. By Friday, the insurance company vetoed a flight home: too complex, too many problems and delays, and they were impressed by Aek Udon’s professionalism. Surgery was scheduled for the next day.

And so I would be crossing Earth’s largest ocean while Amy was under anaesthetic.

A supportive temporary community at an airport gate

I flew from Vancouver to Taipei, to Bangkok, to Udon Thani, distracting myself as well as I could by studying the Thai language. Seat neighbours and stewardesses learned the nature of my journey and treated me generously. I was as well cared for as I could be.

At an airport gate in Taipei, I struggled with balky tech to call Amy after her surgery and failed, and an extraordinary scene unfolded. My phone would not dial out. I asked a couple strangers if they knew how to dial out; they did not, but one of them offers, “Try Skype on my netbook.”

I started by trying to contact the insurance company to see if they had an update, but couldn’t raise them. I really wanted to just call the hospital, because I knew their international relations department wasn’t at work yet, and the language barrier was a deal-breaker without them. A woman who is listening in pipes up, “I speak Thai, I’ll talk to them for you.” And so we called the hospital, and she talked to nurses and then, finally, Amy herself! The whole waiting room was paying close attention by then, and a polite little cheer went up when we connected and Amy came on the line. Everyone heard the whole conversation and I don’t think there was a dry eye in the room. Instant community!

And so for the rest of the journey I knew that Amy was out of surgery, that it had been a very long surgery — about twelve hours! — but she was awake, eating, moving all her limbs, and feeling mentally alert. Knowing that was a real blessing for those last hours.

Bonus amusing drama: crashing the queues in Bangkok!

Despite some good news, the intensity of the trip was still super high, and I was in a big rush in Bangkok. The gap between flights was tight, barely enough time to navigate one of the biggest airports on Earth.

I raced through the terminal from milestone to milestone, backtracking twice, barging to the front of lines like a maniac three or four times, begging everyone to forgive me using a handful of Thai words — mostly “sorry” and “emergency” I think — to indicate that I was not mentally ill or spectacularly rude, just frantic.

And people just got out of my way. Act desperate enough, and people will let you get away with a lot.

I got to my airline check-in and quickly discovered that I’d screwed up: departure was actually an hour later than I thought, and I had plenty of time. A time zone math error. Oops. Bonus drama!

Welcome to Udon Thani — not a tourist town!

On the last flight, from Bangkok to Udon Thani, a stewardess moved me to a more comfortable seat. A seat neighbour helped me with my Thai.

I arrived in Udon Thani stunned, sweating, exhausted, but vibrating with urgency. There was a driver waiting for me with a sign with my name on it, something I’ve only ever seen in the movies. Unfortunately, he was not a limo driver, but an an ambulance driver. He chatted me up in sketchy but enthusiastic English for 20 minutes while my mind nearly melted from the intensity of my anticipation — and the humidity, which felt like being snuggled by a hot, wet dog. And Feb is about as cool as it gets there.

I watched the shabby urban landscape scroll by. Udon Thani is to Bangkok what my little home northern town of Prince George is to shiny Vancouver: a backwater, pragmatic and charmless. It is a “major” commercial center in northern Isan, Thailand, the “gateway to Laos, northern Vietnam, and southern China.” But no one’s going there for fun. I sure as hell wasn’t.

I have this psychological thing where I get really tense the closer I get to a destination, the more I’m haunted by the possibility of being waylaid. The longer the journey, the worse that feeling gets. And this was the longest journey I’d ever taken by far — I had never actually gotten off North America before — and I was doing it for one of the most stressful of all possible reasons. And so that drive was awful. By the time I was in that ambulance, my stress was peaking at what was surely a lifetime high. There were many horribly stressful moments still ahead of me, but I think that drive was the high-water mark. I couldn’t stop thinking about how awful it would be if I had an accident on that drive.

But I did not.

And then, finally, my feet were on the ground in the same building where my wife was recovering from surgery for severe injuries I still did not actually know much about. I was escorted to Amy’s room by Miss Kanjana, the foreign patient liaison and one of the few people in the hospital who spoke English. I was ushered into a large, bright room with one bed in it, and there was Amy, looking … extremely damaged, fragile as a snowflake. Half asleep. But she came to, recognized me instantly, and for a long, long time I knelt awkwardly on a chair by her bed, giving her as much of a hug as I dared, our heads touching, tears flowing freely, each of us trying to reassure the other.

So many injuries! The first substantive clinical update

I talked to Amy’s attending physician on Monday, a lovely guy who spoke good English, and he finally provided me with a complete clinical update. Everything had been a bit sketchy until then. More than a week after the injury, we finally knew the full extent of her injuries and what had been done in surgery. The worst of it:

- Severe brain injury, with unknown consequences at that time, but she was doing surprisingly well with it at that time. “We’re a little surprised she’s been conscious at all, let alone so alert,” I remember him saying.

- Severe burst fracture of T12, plus some crush and/or burst damage to L1, L2, so they bridged all of those vertebrae with impressive chunks of metal on either side of spine, screwed into vertebrae, and a long steel bar screwed into her upper arm with several screws ... “carpentry” surgery! Girl’s got gear!

- A very nasty upper arm (humerus) fracture, with multiple jagged pieces. The sharp edges seriously threatened major nerves and arteries, and the surgeon later spoke to me with great intensity about how arduous a job the repair had been: hours of holding Amy’s arm as perfectly still as possible. At the end of it she had a long steel bar screwed into her upper arm with several screws.

There was a lot more: other minor fractures to her ribs, pelvis, and foot. Major lacerations to her head and both legs, and minor ones all the hell over the place. Her ugliest looking injury was “just a flesh wound,” but it looked like a gremlin had taken a bite out of her shin. It would in time become her second largest scar, after the spinal surgery scars.

But all of that was overshadowed by the more serious injuries, and the pain all blurred together into a roar of systemic sensitivity. To say that she felt sore all over would be true, but cannot do it justice.

The worst “sleep” of my life

I slept in Amy’s room on a rather firm couch, upholstered in vinyl, just a few feet away from her bed. Practically in arm’s reach.

I’d hit peak stress/exhaustion earlier that day, but the first night was brutal, surely the worst night I have endured in almost fifty years (which is saying something, for a severe chronic insomniac). I barely slept, interrupted constantly by Amy’s calls for help, or false alarms — just groaning and crying with discomfort — or by the howls of my own brain. I dozed off many times only to be jolted awake by extreme anxiety, sweating, queasy, my heart not so much beating as painfully clenching and unclenching.

Imagine “that sinking feeling” amplified and repeated dozens of times all night long.

That state felt hazardous, directly and significantly toxic, a clear and present danger not just to my sanity, but to my health and vitality.

We all know and accept that excessive stress is bad for us, but that had only ever been an abstract threat in my life up to that point. I was already under extraordinary psychological pressure when this crisis began. I was in the middle of a career change. But not only had I quit my job just a month before, I had actually done so in a storm of pseudo-legal drama that was not entirely over — ominous loose ends loomed over me. And my new source of income was an idealistic, quirky new business that had only recently and barely started to pay our bills. So I was working like a demon to make sure it would pay.

So that was my extremely stressful context when Amy was injured, and then I went from the frying pan to the fire. A decade later, I can say with great confidence that it was hazardous, and it did hurt me.

Imagining admirable resilience

How would someone tougher and wiser than me handle the intense emotional pressure of that situation?

I remember imagining what it would be like to face the terrible stress of that situation with greater resilience and equanimity. I remember visualizing it as more of an adventure and less of a crisis — instead of cracking under the pressure. It seemed almost in reach; I felt like a sprinter who knew he could probably break his own best time. With just a deft, powerful, mature psychological push, I just might be able to handle the whole thing in admirably unflappable way.

Maybe I could have done it five years before, with five fewer years of severe stress and exhaustion already under my belt. But all I had left was the fantasy. I could imagine a better way, but I could not do it.

Over the next day, I could feel my fantasy of resilience slipping away from me. By the end of my first full day in Thailand, I knew that it was never going to feel like an “adventure,” and I would not cope admirably. It was just too much, too hard, too fast. It was going to suck, and that’s all there was to it.

Setting the scene: Aek Udon Hospital

Aek Udon is a private hospital in a 1990s-era building of about a dozen spacious storeys. There is a huge central courtyard, surrounded by wide, shady balconies on every floor — a fairly pleasant place for me to spend time when I had the chance. The hospital is attached to a Western-style hotel, where most family members of foreign patients stayed, but I never even poked my head into that — there was talk of it for a few days, but Amy was so badly injured that I was needed to be in the room nearly full-time as an amateur nurse. (After a couple days, the hospital gave me another bed to sleep in, so I didn’t have to continue sleeping on the plastic couch.)

I think that Aek Udon served wealthier locals in addition to focussing on medical tourism; it was a place where foreigners can, for example, get their eyes lased for a fraction of what they would pay at home. But Aek Udon was also a serious, full-service hospital, and it mostly felt like it — other than the fact that hardly anyone spoke any English, it was just like any decent hospital anywhere, with lines on the floors and constant announcements, nursing stations and nurses everywhere, the smell of disinfectants, big swinging doors, people being pushed around in wheelchairs and on beds.

It is easier to say what made Aek Udon different from the hospitals I have known in Canada:

- They were nowhere close to being at capacity. At least a couple floors were completely closed down.

- Hardly any sign of any language other than Thai, and almost no English at all, which was odd for a hospital so obviously interested in attracting wealthy customers from around the world.

- A really excellent cafeteria. Their small selection of Western food was hilariously bad, but the Thai food was truly terrific, though nothing like Canadianized Thai cuisine. I’d go there for dinner tonight if I could!

Setting the scene: Udon Thani

It took me more than a week to leave the hospital and do any exploring, and I never did more than a few modest walks, but it was enough to get a sense of the place.

Both hospital and hotel were by far the largest structures in the area at that time. The city around them was showing signs of development, odd islands of conspicuous affluence in a shabby ocean of urban poverty — not the folksy poverty of remote farms and villages, but the noisome and ramshackle poverty of a city that isn’t even trying to impress tourists. Browsing through recent pictures of the place, development obviously continued and it looks nicer now. But Udon Thani in 2010 reminded me of a steamy Thai version of my own hometown, Prince George, a logging town in northern Canada, with the same kind of practical architecture, but much poorer. Where PG was cold and dry and smelled like pulp mills, Udon Thani was hot and humid and smelled like piss and smoke. It was all cliches of urban poverty:

- intersections clotted with crappy old scooters

- sad stores with bizarrely random inventories: a stack of cars tires between of a rack of cosmetics and a fridge full of cuts of meat and soft drinks

- a dirty toddler standing in the gutter and sucking on a limp little lizard

- whiffs of sewage alternating with delicious-smelling street food that looked like it could give me diarrhea just from passing by it

- fly-covered market meat spread out on tarps on the ground

And so on. I couldn’t go ten feet without xenophobically thinking “how can people live like this?!” It was all so embarrassingly predictable and distasteful that I didn’t want to talk to Amy about it. She is a seasoned traveller, amateur anthropologist, and keen student of culture and language. Whereas my instinctive reaction to much of this was surges of squeamishness, she would have been talking to people and clapping gleefully at the chance to sample that street food — which she’d get away with eating, somehow.

Two vivid memories from my longest walk in Udon thani

After blocks of hovels and street markets and “restaurants” with pairs of plastic tables, I stumbled on a shiny, modern, western-style mall, which looked like an alien mothership that had landed in the middle of the city. A dark, reeking alley divided the poverty from the wealth: a huge, smooth white wall looming on one side, juxtaposed with a mess of crumbling brick and laundry lines and bent TV antennae sulking on the other. I went into the mall, of course, and it was like another world in there. Surreal.

On my way home, I found myself cutting through a parking lot. There was a large group of young men huddled around something on the far side. I avoid huddles of young men, but this was Thailand in the afternoon, not Tijuana at 2 am, so I put on my most confident face and stride and hoped I wasn’t about to get stabbed for my wallet (which probably had enough in it to buy whatever building was beside us). Some watched me approach, their faces popping out of the huddle to see the approaching foreigner, while others continued to focus excitedly on … something. My mind reviewed the possibilities I’ve learned from the movies. Snake fight? Some kind of gambling? Beating the hell out of someone? No! None of the above! They proudly opened up their circle to show me…

An ice sculpture.

A guy in the middle was working on an ice sculpture of a swan, and it was an impressive one. The building beside us was a hotel. They were all hotel employees, and they were eager to show the Canadian their handiwork. A camera was pushed into my hands. Few words of English were spoken other than “selfie?” and “please” and “Canada!”

So that’s the story I focused on when I got back to Amy.

The best of all possible disasters

The extraordinary misfortune of Amy’s accident was followed by a parade of best-case-scenarios in rehab. It was a miracle that she wasn’t paralyzed, a miracle that she wasn’t in a coma, a miracle that she had no serious nerve damage in her arm, and so on. For a long time, almost everything went just about as well as it possibly could have, given the severity of her injuries. Long term consequences are for later in the story, but in the first days, weeks, and months, it was like playing Twister with fate and winning, precarious but victorious.

In retrospect, it seems like everything went quite well.

At the time, however, everything that turned out well was a surprise preceded by dread. For instance, infection is a fairly common post-surgical complication that can sabotage otherwise successful procedures. That danger, one of several, slowly faded over a couple weeks, but it hung over the scene like a dark cloud for many days.

The first week was a blur of caretaking and problem solving, the logistics of making hard things work. Amy was odd company in those first days, and remembers nothing. The best of her shone through occasionally, her optimism and whimsy, her fascination with other cultures apparent even when wracked with pain, practicing her Thai every time a nurse was in the room.

Minutiae like brushing teeth and embarrassing stuff like dealing with the personal plumbing was unbelievably time-consuming. Meals from the hospital kitchen were fun and tasty but also incredibly tedious. There was an almost constant need to help her move in bed to prevent pressure sores and keep her from going nuts. She was getting reeeeeally tired of being in bed, and being still. It was all hard enough, but we were also doing it all in a strange, faraway place and trying to solve two-thirds of our problems through a language barrier.

Despite all the caretaking clutter, there was downtime. For entertainment, we binged Lost on DVD — which was, I think, our first ever true binging on TV.

Tube free and stir crazy

By the middle of week two, medical progress was clear. Getting rid of all her tubes was a big step: no more IV drip, catheter, or wound drains. That all made her seem much more normal.

One morning was largely devoted to getting her fitted with a back brace and teaching me how to help her get into it, and then out again. Once it was on, it was an impressive rig, chic beige leather and lots of aluminum.

Much later, I studied spinal bracing and learned that it’s actually astonishingly difficult — maybe even impossible — to actually “stabilize” a fractured spine, even with titanium implants, let alone an external brace. Experts cannot agree on whether or not any of it is actually helpful, and there are clues that the body is astonishingly good at recovering from fractures without any physical stabilization at all.

But it sure seemed like a good idea at the time, and so I learned how to put the brace on her, and learned to count in Thai with the many straps and buckles: “noong, song, sam, see, haa, hok, jet, paet, gao, sip!” (It’s really hard to spell those “phonetically.”)

Despite the brace, she was still days away from actually standing up, and that would prove to be a dramatic challenge when it finally happened.

A trip to the dentist

On Thursday that second week, we discovered a broken tooth! She lost half a molar in the accident. How messed up do you have to feel in general to be oblivious to losing half a molar? She did know that “something” was off on that side of her mouth, but we didn’t look into it carefully until more than a week after her surgery. The tooth had a filling which was still in place but precariously overhanging the space that used to have the other half of the molar.

The tooth was repaired by a dentist in the hospital a few days later — a big deal under normal circumstances, completely overshadowed in that situation.

Living at the hospital as things got more normal

As things settled down, I had a great need to escape The Room. I am a typical writerly introvert; I seek solitude, keyboards, and coffee. The hospital was mostly a quiet place and offered three good options: the atrium for solitude (and a decent atmosphere), the cafeteria for adequate coffee and partial solitude, and a queer little coffee shop in the basement for good coffee strong enough to strip paint.

Aek Udon has a hollow centre, like a doughnut, open to the air: sky above, trees below in the courtyard. A large area on each floor is adjacent to this open area, clean, natural lighting, and mostly abandoned. It was my office space for the duration of my stay. The tables could have been a little more comfortable, and I didn’t love being exposed to sky because mosquitoes can come from the sky — the closer you were to the courtyard, the more likely you were to encounter them. And dengue fever is an endemic mosquito-borne illness in that region, and it’s terrible.

But an introvert’s gotta do what an introvert’s gotta do. Damn the mosquitoes, full speed ahead! I only got bitten a couple times. I did not get dengue fever.

The coffee shop in the basement was an eclectic place run by a tall, skinny young Thai lady who spoke decent English and enjoyed practicing it with me. I didn’t discover her shop until I started exploring the hospital in week two, and I was there daily after that. Each day she’d teach me a Thai word, and I’d teach her an English word, and that was a nice ritual. Like many shops in Udon Thani, it was hard to define hers: she sold a quirky mixture of clothing, arts and crafts, homemade and snack foods, including the most disappointing mango I’ve ever eaten: the packaged slices looked mouth-watering, but they turned out to be pickled mango, as sour and bitter and tough as lemon rind. What a betrayal that first bite was!

And coffee, of course! She made amazing coffee, or at any rate the most potent coffee I have ever had, black as tar with a thick puddle of condensed milk at the bottom, in a huge plastic cup like we see only for bubble tea here. I didn’t realize the danger at first. That coffee was how I first learned that too much caffeine can be brutal, and a terrible sauce to pour on jangled nerves. It was like I assume a cocaine high feels like for a couple hours, followed by mere heart-skipping queasiness for hours.

Soon I learned to drink only a third of a cup at a time, even that could be a bit rough. But it sure was tasty!

The hospital’s totally justified anxiety about payment

Almost every day I talked to “Miss Kanjana,” the ambassador to foreign patients. Miss Kanjana was lovely. She did a great deal to ease our passage through her world. We are forever in her debt, and probably more than we know.

Poor Miss Kanjana — she was worried the whole time. It was her job to help us out as much as she could, but it was also her job to make sure the hospital got paid. We had a valid insurance policy and assumed there would be no problem paying the hospital. Miss Kanjana wasn’t so sure.

“We’ve seen quite a few insurance companies simply fail to pay,” she told me right away.

“We will not tolerate that!” I assured her. “And I don’t expect a problem. They have been very helpful and accessible so far. I’m sure there won’t be a problem.”

Ah, sweet child of summer. Such optimism! They didn’t pay while we were there, and Miss Kanjana’s concern grew with every day, and she was clearly extremely agitated about it by the time we left. But I was highly preoccupied with the logistics of getting Amy home, and continued to assume it was just a matter of a relatively short wait before the insurance company coughed up.

Not only did the insurance company fail to pay the hospital, it took two fucking years. Tragically, during that time, Miss Kanjana was fired for failing to secure payment for a substantial invoice — and I am horrified and ashamed by that outcome to this day. Amy’s surgery and other care cost about CAD $13,000 — a bargain for what she received, an almost comically small fraction of what the same care would have cost in the US, but it was beyond our means at the time.

I’ll finish the payment story later.

The challenge of getting home

Turns out that taking an international flight with a serious injury has a difficulty level of “insane.”

Like a ship captain, airline pilots have substantial authority over their craft; they are legally responsible for injured passengers, and so they can and do refuse to take them on unless quite strict requirements are met. In general, injured passengers need to be able to stand and walk, even if they need a wheelchair in general. And/or they must fly with a nurse. If the airline or pilot is not fully satisfied that an injured patient is safe to fly, it ain’t happening.

And if you fly with a nurse — with two first class seats — the cost is extreme. The flights we eventually secured would cost a total of about $25,000 — almost double the cost of Amy’s hospital stay.

And so arranging a flight home started to look like a major challenge. Two weeks out of surgery, Amy still hadn’t stood up, let alone walked. Flying home on a stretcher was even more astronomically expensive and the insurance company basically refused to do that. So it became a race to get her up and walking enough that she could handle the flight home.

Of course, we wanted her to achieve that as soon as possible regardless of the flight. But we basically had to gamble and make all the arrangements before we knew that Amy would be physically able to do it. Which turned into quite the nail-biter!

“Standing” up — adventures in tilting

Cardiovascular systems slack off when they aren’t challenged — a truism of fitness that becomes a more glaring fact of biology when you lie down for three weeks. If you just try to stand up and go for a walk on day 22, you will fall down. The heart just refuses to go back to work after that long a holiday.

Getting Amy back on her feet meant being carted downstairs to the physical rehab clinic on her mobile bed, being painstakingly transferred to a tilt table. Just that is rough when you’ve only just started to heal from multiple serious injuries and major surgery.

And then the main event: tilting! A tilt table does what it sounds like: you get strapped on, and then it swings your head up and your feet down around a fulcrum in the middle. But you can’t just go crazy. The whole point of the tilt table is that you start easy: just 45˚ for a minute or two.

The first time, Amy turned white as a sheet within 30 seconds, then just a little bit green (apparently in some people the green tinge is produced by the combination of deoxygenated blue blood and yellow skin tones).

And then we did it all again the next day, but 60˚ for 5 minutes. And so on.

From tilting to walking

When you know you’re supposed to be able to stand and walk for your flight home in just a week or two at the most, the rate of progress on the tilt table did not seem adequate. But it accelerated. On the third day, she tolerated 70-80˚ for several minutes... twice. And on the fourth day, she went to 90˚ for several more minutes.

On the fifth day, assisted walking! She took six steps. She couldn’t remotely do it by herself yet, but the better things got, the faster they got better.

Just two days later, 80 steps! Still supported, though.

It seems biologically interesting to me that just a few minutes per day of partial tilting is apparently enough to provoke the body to prepare for actual standing and walking.

This was all very time-consuming, and Amy was in the rehab clinic a lot, and loving it. There was one young Thai physiotherapist who spoke good English with a Texan accent, which was odd — she had done a work exchange program in Texas. So she was “Miss Texas” for the rest of our stay. A small flock of other physios and nurses were are all hopeless at English, but Amy just saw that as a challenge: she spent pretty much her entire time there quizzing them on the Thai and Lao languages. Amy generally seems to regard her stay in the hospital here as being one big language lesson.

After her power to walk was established, Amy only needed me to put on the brace, and then she was off like a shot, doing all kinds of things that had been impossible without major assistance just a few days before. Funny moment, for example: I was still standing by, just in case, and she says, “Can you help me wash my hands?” She had needed me for that regularly.

“Or you could just wash them yourself,” I said. “You’re standing near a sink.”

“Oh,” she says. “Right! Yeah, I can do that now!”

Real progress!

The miracle of a medical escort

Almost the day before departure, we still thought Amy would be on a stretcher on the plane, an even more astronomically expensive way to fly a hurt person home. But, at the last minute, our insurer decided to save some money and have Amy fly like a healthier person — but in a first class seat where she could be fully prone. Plus, of course, an adjacent first-class seat for the nurse.

But that decision caused complications.

Our medical escort, Alex, was a diligent and professional male nurse from Toronto. He met us at Aek Udon hospital, briefed us, and rode with us in the ambulance on a stretcher. The first leg of the journey was going to be the hardest: Amy would have to sit upright for the hour-long flight from Udan Thani to Bangkok. And yet she hadn’t yet done that for more than a few minutes at a time.

The entire thing almost fell apart before it even started. The airline manager at the Udon Thani airport was having none of it. While we anxiously sat nearby, we watched the nurse work. The manager did not want anyone as injured as Amy on his plane, and didn’t appear to be familiar with how medical escorting worked. The nurse put on a virtuoso performance, demonstrating expert diplomacy and knowledge of airline regulations, the law, and medicine. He explained, painstakingly, why the airline manager should allow Amy to fly. There was a mixture of English and Thai throughout.

This took almost an hour. It was epic.

The nurse came over to check in with us a couple times, calm but stone-faced. (Remember, Amy had not yet been seated upright anywhere near this long.)

“He’s quite nervous,” he said. “We see this in smaller towns, at smaller airports, where they don’t see many medical escorts. It’ll probably be easier in Bangkok, but you see what we’re up against. Red tape everywhere, and human nature.”

Medical escorts really earn their pay. They aren’t just nurses, they are travel logistics experts. It was impressive as hell, and Alex achieved his goal. He strode over to us with a big grin: “Let’s fly to Bangkok!”

There was another airline gauntlet to run, but the hardest part was done.

One really odd night in Bangkok

Amy did well on that first, hour-long flight, but she was in pain, and was relieved to be transferred to a stretcher after the flight. We got another ambulance ride to some mysterious accommodations nearby — some kind of dormitory for travellers with special needs? In all seriousness, I think it might have been a hospital. The memory is hazy, and Amy is no help — she’s missing a lot more of these experiences thanks to the head injury.

All I remember is an institutional vibe; a long, featureless white hallway outside the door; a small window, through which we could see a bit of Bangkok skyline.

We passed a strained night, isolated and quiet except for the hums and whirs and bangs of an alien building, at the mercy of humans we barely knew, waiting to take a flight the next morning that we might get barred from. When we asked Alex what would happen if they wouldn’t let us fly, he calmly replied, “Well, let’s just make sure that doesn’t happen.”

Putting on an ambulation show for the airline

So the next morning we were up early to catch our flight, and got our marching orders: we were going to drive to the airport and put on a show.

Animal parents sometimes pretend to be injured to distract a predator. Amy had to pretend not to be injured — to “distract” the airline authorities from the reality that she was still quite severely injured.

“This is smoke and mirrors, pure psychology,” Alex explained. He gave a speech he had obviously given before to other escortees, and it went something like this:

“We’re going to transfer you to a wheelchair. No one at the airline can see you on a stretcher — there’s no chance you’ll fly if they do. Even the wheelchair and a medical escort will alarm the ticket agent, and she will call the manager, but this is what we want: we need to put on a show for the manager. You’re going to demonstrate that you don’t actually need the stretcher, and that you’re flying first class because you’ll be more comfortable, not because you have no choice but to lie down. If she can see you walk, even a few steps, it will persuade them that you are fit to fly, regardless of what it says on your medical chart. So you have to be convincing. Walk as normally as possible! Don’t look sick or pained if you can possibly manage it.”

And so that’s what we did, and it basically went down exactly like Alex predicted. The manager did briefly put up a bit of concerned resistance, but was almost comically persuaded as expected: “Well, I guess since she can walk that well…”

Apparently the airline managers do not know the tricks of the medical escorts.

The flight itself

Once we’d cut through the last of the red tape, it was smooth sailing. We flew from Bangkok to Hong Kong to Vancouver, via Hong Kong, and were treated well the whole way. In the airline’s eyes, Amy was a charming patient with special needs. And Alex was an extremely competent expert who knew all the best tricks for getting the most out of a flight.

We had some time to kill in Hong Kong and we did it style in the first-class lounge. I remember we had ice cream. Aside from Amy being in a wheelchair, enjoying first class amenities, and having Alex tagging along for god-only-knows how many dollars per hour, it just felt like normal travel.

I didn’t get a first class seat — the insurer wasn’t about to pay for that, and I can’t even blame them — but Alex generously swapped with me for a couple hours, so that I could hang out with my wife, have a nap in the fully reclining seat, and experience air travel the way it was meant to be experienced.

I think we were treated well even by first class standards. I suspect that stewards and stewardesses probably like to be of service to muggles who invade the first class section for special reasons like this; no doubt we’re a delight compared to all the entitled jerks who are probably all too common in that domain.

It was smooth sailing all the way to the “wet” coast of North America. There were no medical issues. We actually enjoyed ourselves, despite all the challenges that we knew awaited us on the other side of an ocean.

Welcome home!

At Vancouver International Airport, a Canadian ambulance delivered us all the way to our fourth floor apartment in downtown Vancouver. One of the paramedics was a clownish, amiable guy full of dad jokes; we’ve run into him a few times over the years since. We were punchy with fatigue, and he was just the right combination of calm and effervescent, and it made an nice impression. More good service!

Amy’s mother met us at the door, and was vibrating with concern and eagerness to help.

This was before we were all armed with iPhones, so I don’t think we’d been in communication much. Maybe I was carrying my very first, an iPhone 3, which seems like a Flintstones phone now. (Interestingly, my records show that I bought a 3GS just 48 hours after getting back to Vancouver.)

Our journey had gone about as well as we possibly could have hoped. There were no medical complications. Amy did not suffer egregiously, as she might well have. She was simply utterly exhausted.

“You’re going to be tired for a long time,” she was told by the first Canadian physician she saw, a couple days later. “People don’t realize how much energy an injury like this steals from them. Don’t underestimate it.” And she didn’t, and it was indeed an ordeal: Amy was constantly exhausted for many months. It took a year before she seemed mostly recovered, but I don’t think she ever finished: she’s been significantly more prone to fatigue ever since.

The aftermath

The main part of the story has now been told, but an accident like these has many consequences, so I’ll wrap this up with a few anecdotes about some loose ends.

The Canadian doctor

This is just a funny/interesting thing that happened almost immediately after we got back. That doctor who warned Amy about exhaustion got off on the wrong foot with us. He was a very old orthopedic surgeon, who seemed well past retirement age. He was cranky and disinterested and dismissive for the first few minutes of our appointment with him. He scoffed at what the Thai surgeon had done: “We never would have installed hardware for this!” He seemed to think Amy’s needs were minimal at this stage and insinuated we might be wasting his time. With a major spinal fracture? Bizarre.

“But I’ll have a look at the x-rays and read the files a little more carefully. Give me a few minutes, I’ll be back.”

When he returned, he was a changed man. His eyes were bright. He made eye contact:

“I really owe you an apology. I should have looked at the x-rays before your appointment, and I shouldn’t have been so dismissive. I had no idea how severe this injury was! Wow, you really crushed that vertebrae something awful. I shouldn’t have talked trash about the Thai surgeon: not only do I think he probably did an excellent job, but this injury is... well, he did the right thing. I definitely would have done something similar.”

Well alrighty then. 😉

My wife had an actual screw loose

Amy’s back contained a bunch of surgically implanted titanium — bracing on the inside, two vertical bars that spanned the broken joint like rails attached to fence posts driven into the bones above and below. We always just called her implants the bars, as in “How are the bars feeling today?”

I wondered all along if all this bracing was really doing anything, and that’s a fascinating medical question I’ve explored in detail on PainScience.com. Her experience was inherently interesting, and full of lessons relevant to back pain.

Amy was stooping over in the bathroom about a month after homecoming when something startling happened: she squeaked like a dry-hinge! It was a metal-on-metal sound, a bit quiet — muted by a little flesh, but unmistakable. I asked her to stoop several times in a row. squeak squeak squeak A reproducible metallic sound!

One of the bars had come out of its post socket. This was plainly visible on an MRI scan of her back — but missing from the radiologist’s report. I found it myself, staring at those magical black and white transverse slices of my wife’s back, which clearly revealed cross-sections of a screw (so unlike any anatomy!) floating in the wrong place, the end of the of one bar well out of place… and the other one on the verge of coming loose as well. I am proud of making that discovery, even though it is not really as amazing as it sounds. Certainly it’s a minor embarrassment for the radiologist, but mostly his attention was properly on my wife’s bones and spinal canal, not so much her implants.

The find was soon confirmed by a surgeon, who was more amused than shocked. “It’s rare. Less than 5% probably,” he explained. “But it does happen, and it’s really not that big a deal.” The bars are simply an internal brace, and are more or less useless dead weight once the bone has healed (if not long before that).

Two years later, Amy had the bars removed. They had become bothersome — a constant, nagging, uncomfortable presence. The procedure and recovery went well, other than the formation of an impressive seroma, a bunch of fluid trapped under the skin, common after surgeries. It was about the size and texture of a small breast. Seromas sometimes cause trouble, and consequently we aborted a planned trip to Hawaii — because the last thing we wanted was to travel to the US with a well-documented surgical complication in progress. If it got infected while we were in Hawaii, it would mean big trouble!

So we stayed in Vancouver, and it behaved, slowly fading away over about six months.

For a while, the seroma was affectionately known as Third Tit or Back Boob, so it was good for a laugh, at least.

Was the hospital bill ever paid?

Yes, but only by applying substantial pressure after a long, embarrassing, stressful delay. The company was TIC (literally for “The Insurance Company,” now defunct). They dragged their feet, taking weeks to respond to any inquiry, and invariably with some red-tape excuse when they finally did. They also tried hard to pass the buck. First they tried to get the government of Canada to pay the bill, an effort we correctly assumed was doomed. Then they switched to trying to get the bill to be paid by insurer for the company that owned the truck Amy crashed in, and many of the delays were attributed to trying to negotiate with that company.

Eventually the failure to pay become so absurd and frustrating that Amy wrote a letter to the CEO, basically trying to shame him into taking care of it — which actually worked. A few days after putting the letter in the mail, we got a call from the vice-president of the company, who was friendly and conciliatory and (most importantly) did not just promise to get the bill paid, but he literally arranged for it right then: “I don’t want you to wait another day for this, so I’m going to get my secretary to transfer the funds to the hospital right now, while you’re still on the phone with me.”

A memorable evening with Steve Martin

Amy had major memory gaps around the accident. Her head injury was serious — more about this soon — but for a long time the only problem we were aware of was the memory gaps, and we kept discovering new ones, missing events from the weeks and months before the accident.

One of them was hilarious.

On July 23, 2016, six years after the accident, we went to see Steve Martin and Martin Short in Vancouver. Great show, lots of fun. And there’s a really good story here. The setup is a little complicated, but hang-in there: the punchline is precious.

A few months ago, when my wife Amy first heard about this tour, she was really excited and described it as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see Steve Martin. Amy’s a huge fan and Steve’s getting old (70 at the time) and who knew if we’d ever get another chance? So she was pretty revved up about it: “We have to see him!” Okay, sure, but there’s just one problem…

It couldn’t be a once-in-a-lifetime experience, because we already saw Steve live in late 2009. And that was a big deal for Amy! But here she was talking like this show was going to be the first time, like she had no memory of it. I gently brought it up.

And she didn’t believe me. She thought I was pulling her leg. Amy has zero memory of her accident, and she’s had a lot of memory problems ever since, but always trivial stuff.

But Steve Martin is important to Amy and she could not believe that she couldn’t remember seeing him. With some effort, I managed to dig up proof: a tour schedule and a selfie in the Orpheum on the right night. We were there! Amy was amazed, because this truly meaningful thing had somehow gotten away from her, stolen by head injury. Poignant, right? She was so lucky it wasn’t worse, but still. But then there’s this…

The name of Steve Martin’s current touring show is… wait for it… this is so good…

…

…

🤣 Amy thought that was so funny that she sent a message to Steve Martin telling him the story. It’s unlikely that he actually got it, but if he did… definitely his kind of joke!

“I can’t brain today”

Amy's brain injury was worse than we knew at first. Her brain was peppered with scars, damage plainly visible on a high-contrast MRI, quite unusual in someone who seems to be doing pretty well. In general, if your brain has tears in it like the knees of an old pair of jeans, you're going to struggle with all kinds of things that brains are normally needed for, like thinking, talking, remembering, and dancing.

But Amy seemed mostly fine. Sure, there were big memory gaps around the accident, but that didn't seem worrisome or surprising. And she was a little spacey at times, and her conversational style was a bit scattershot — but that was just a modest amplification of well-known character traits. My wife has always been prone to nonsequiturs. Half the things she says to me are the back end of a train of thought I wasn't aware of.

So what sorcery was this? How can you rip up a bunch of neurons like that, and cope so well?

I have no idea. But it did slowly became clear that she was in fact in worse shape than I had realized.

The first thing we noticed was that she wasn't forming new memories well, and particularly not for low-stakes input like movie plots. It became a bit of a running joke that Amy could get really good "value" of films, because she could see them repeatedly, enjoying them like a new film each time. On many occasions I’ve re-watched a good movie an extra couple times, because she can’t remember that we’ve even seen it, let alone what happened. I think we’ve seen Live. Die. Repeat. about 8 times.

But eventually that stopped being amusing. Bit by bit, it became more ominous.

It stopped feeling like a running joke to me the night that I came home and Amy excitedly suggested a movie night, and her title of choice was a movie we had watched really recently. And it wasn't just that she was forgetting the film, but the fact that we had already watched it together, twice, in less than a month, first in the theatre, and then a rental. (Ironically, I cannot remember what the film was now.) I had been unsettled by the second viewing, but completely forgetting two previous viewings was in a new league. Chills ran up my spine.

We watched the movie a third time, and nothing clicked for her. For her, it was the home premiere. The possibility that my wife might be at high risk for some early onset dementia became very real that night.